In recent months, it has been difficult to avoid exceptional events hitting the headlines, with conjecture rife around the impact of COVID-19 (coronavirus) and the subsequent increase in volatility wreaking havoc within the commodity markets, the next headline-grabbing twist always seems just around the corner.

Within the crude oil world, phrases such as “price war”, “Black Monday” and “negative pricing” are far from the expected norm and portray a bleak and ominous landscape. We will look at how a surge in the use of such fatalistic language has been influenced by a disruptive shift in all three primary market price factors: Supply, Demand, and Storage.

Supply

In early March, the OPEC+ alliance of oil-producing nations called an extraordinary summit to discuss the rapidly escalating situation globally. With COVID-19 infections spreading at an unprecedented rate, and soon to be declared a pandemic, it was envisaged that unilateral production cuts would be agreed upon to stem the tide of falling oil prices.

However, fraught discussions ended in stalemate, with Russia refusing to accept the level of production cuts proposed by Saudi Arabia. Within days, state-owned Saudi Aramco announced a 2.6 million bbl/day ramp in production, Russia followed suit with a 300,000 bbl/day increase, and a standoff for market dominance began, hitting hardest the US shale market, where many participants were already operating in a precarious financial position [1].

Despite the universally negative ramifications, both parties remained firm for a little over a month on their renewed tactical approach. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has previously calculated that to balance the Saudi national budget, they must achieve c. 80 USD/bbl, however the chosen stance saw the prevailing Brent market price crash to around one-quarter of that.

On April 12th, a ceasefire was introduced, and a “historic” agreement reached (by video conference, of course) to cut production by 9.7 million bbl/day across May and June, roughly 10% of global demand pre-pandemic. As we will see from the Demand outlook, this was too little, too late [2].

Demand

The locality of COVID-19 epicentre distribution has emphasised the severity of factory output decline since the virus’ inception. The United States, European Union and China represent not only viral hotspots in the initial months of the pandemic, but as industrial behemoths are also the world’s largest oil consuming nations:

Rank | Country/Region | (bbl/day) |

1 | United States | 19,690,000 |

2 | European Union | 12,890,000 |

3 | China | 11,750,000 |

… | ||

Source: CIA World Factbook [3]

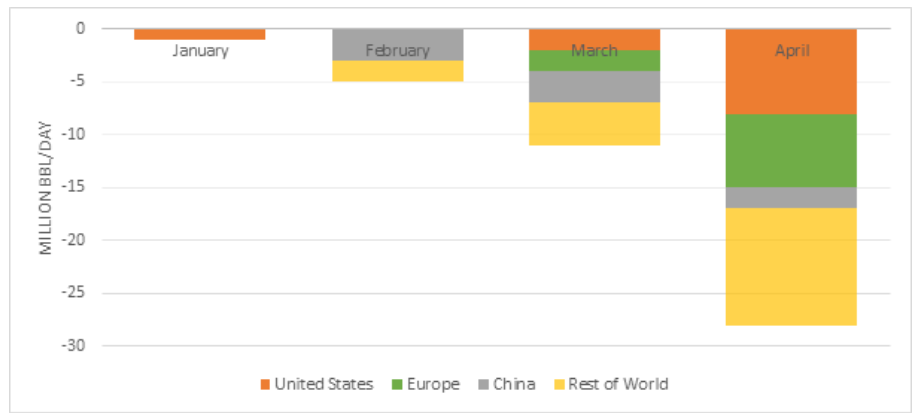

As January drew to a close, factory shutdowns throughout Q1 and beyond saw a decisive downturn in demand across the board:

Change in Monthly Oil Demand (2019 vs. 2020)

Source: International Energy Agency [4]

During such periods of rock-bottom pricing, you might expect to see a wry smile cross the face of downstream refined product consumers. Step forward the CFO of an airline where jet fuel contributes over a quarter of overall operational costs, or the average 1.2 vehicle owning household, watching as pennies roll off the price of fuel at the supermarket forecourt. However, to quote the late magician Tony Corinda:

“good timing is invisible, bad timing sticks out a mile”

With travel restrictions in place globally, borders closed and lockdown protocol initiated to curb the spread of infection, there is little scope to monopolise on the glut of cheap oil. Most airlines have grounded their fleets or significantly cut capacity, furloughed staff and are facing substantial losses from hedging their predicted jet fuel requirements at a significantly higher market price (see Ryanair who hedge 18 months out, through forward contracts [5]).

Storage

The most eye-catching headline of the saga to date has been “negative price” oil. On 20th April, future contracts for WTI Crude crashed to a low of -$37.63, as the date of delivery drew in. Making laymen dream of stashing a few barrels in the garden shed, this event drew a spotlight to the third contributory factor in our Oil Price Trifecta: storage.

Physical delivery of WTI Crude Futures takes place in Cushing, Oklahoma (driving distance from the capSpire Tulsa office). This hub of activity has been dubbed the “Pipeline Crossroads of the World” and has in the region of 90 million bbl of storage capacity. However, with the reduction of consumer demand saw a rush for storage in April and there was no room at the inn [6].

That has not stopped eternal optimists finding opportunity amongst the ruin. As well as some nations investing in building their strategic oil reserves, some opportunists have acted on developing a new “space race” as they look to find storage capacity where previously there was none. Some of the more ingenious solutions include Swedish salt caverns, train cars [7] and even record levels of in-transit storage as oil tankers remain perpetually offshore [8].

How Will Markets Recover?

It remains to be seen how equilibrium will be restored, with each of these price factors all straying from the norm, but it is clear that with many organisations throughout the industry trading below their respective profitable thresholds, the current trends remain unsustainable. This makes it as important now as ever to look for opportunities to operate in a better way and find ways of making optimisations across the value chain. capSpire provides the unique combination of industry knowledge and business expertise required to deliver impactful business solutions. Trusted by some of the world’s leading companies, capSpire’s team of industry experts and senior advisors empowers its clients with the business strategies and solutions required to effectively streamline business processes and attain maximum value from their supporting IT infrastructure. For more information, please visit www.capspire.com.

About capSpire